- 2023 goal setting uncertainty. Particularly in the retail industry, recent economic and market uncertainty are expected to impact fiscal year 2022 incentive plan outcomes and create goal setting challenges in -2023 and beyond.

- Approaches to address risks. Establish wider performance and/or payout curves, introduce strategic or operational metrics, separate or shorten performance periods, and consider using more relative metrics.

- Ensure future durability. In contrast with the temporary actions taken to immediately respond to the pandemic, retailers should consider the long-term durability of any incentive plan changes in response to a more prolonged period of uncertainty.

Economic headwinds and volatile markets have significantly affected fiscal year 2022 (FY22) incentive plan outcomes in the retail sector.

What's more, uncertainty surrounding these external factors creates challenges for retailers to appropriately set goals for fiscal year 2023 (FY23) and beyond — in both short- and long-term incentive plans. This uncertainty has led retailers to evaluate both minor adjustments to and wholesale redesigns of FY23 incentive plans, many of which echo changes made during the pandemic.

The key difference is retailers are evaluating the long-term durability of these actions, compared to the more temporary “one-time” actions made in response to the pandemic shock. To account for this difference, there are potential incentive design changes that are worth exploring to mitigate uncertainty in FY23.

Establish Wider Performance/Payout Curves

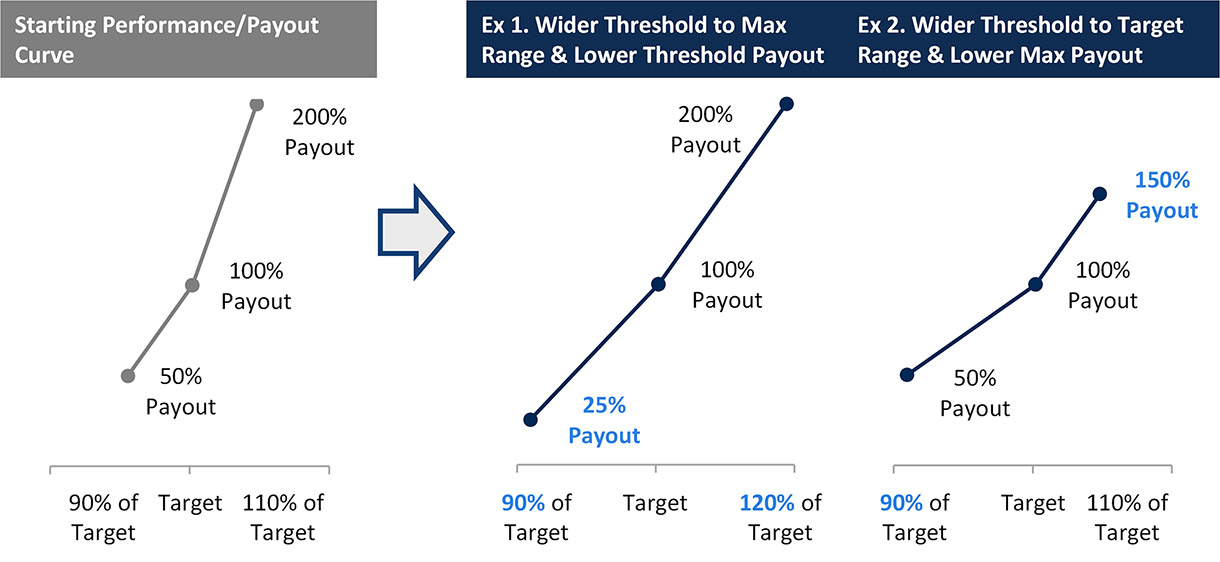

Extending performance/payout curves is the most common and direct approach for retailers with established threshold-target-maximum performance curves to address goal setting uncertainty. Target performance would continue to be calibrated relative to budgets and external communications, while the threshold to maximum goal range (typically set as a percentage of target) would be increased to cover a wider range of performance outcomes. A wider goal range may also require adjustments to the corresponding threshold and maximum payouts.

Illustrative example of approaches to adjust a performance curve:

The lower threshold goal reduces the risk of no payout if macroeconomic conditions deteriorate, but internal performance remains resilient. The maximum goal and payout balance against the adjusted threshold goal is such that if macroeconomic conditions improve, results still need to be well above budget to earn a maximum payout.

This approach is most effective for managing the external exposure of incentives tied to the income statement. The adjusted performance range will depend on the selected metric. A bottom-line metric requires a wider range as a percentage of target, while a top-line metric typically exhibits a narrower range as a percentage of target.

Introduce Strategic or Operational Metrics

Strategic metrics allow for performance evaluation based on factors within a management team’s control. If a board anticipates uncertainty, strategic metrics provide an opportunity to evaluate performance quality in addition to the formulaic portion of a bonus plan tied to financial results. For example, stakeholders may consider a slight miss on earnings during a recessionary year to still be exceptional performance. Conversely, meeting a 2% sales growth target in an inflationary environment with the ability to raise prices significantly may be viewed as weak performance, especially if sales growth is outpaced by expense growth.

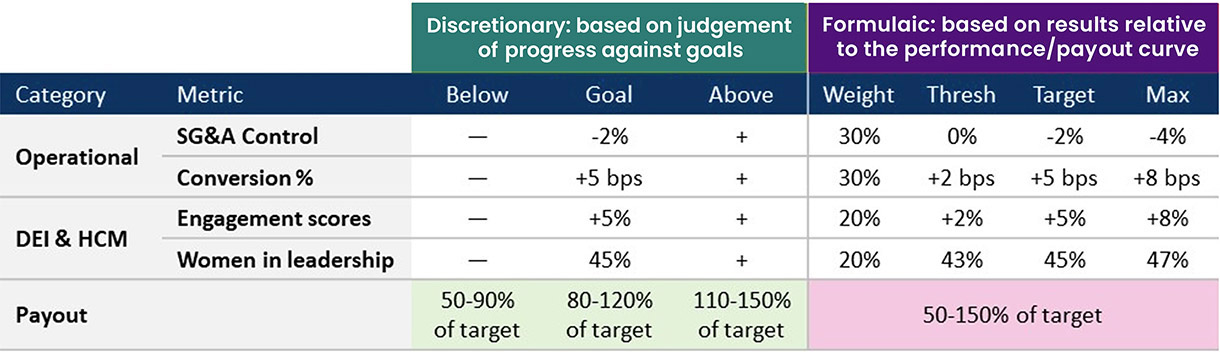

The best strategic or operational metric(s) to add depends on a company’s specific situation — no singular “correct” metric exists. That said, strategic/operational metrics are most appropriate when (i) a strong business rationale exists to measure the selected objectives and (ii) the selected objectives emphasize key steps to deliver financial targets.

The most common strategic metrics among retailers are operational KPIs, such as inventory, omnichannel growth, expense control, and/or an internally-focused, qualitative scorecard that includes measures like success in a certain channel/customer group or an ESG-focused metric.

Companies that adopt strategic metrics typically weigh them at 10-25% of the overall bonus plan, with the remainder typically tied to financial metrics (e.g., sales, earnings, or margins). The strategic component is generally set up as a scorecard with performance determined in one of two ways: (i) discretionary evaluation relative to target goals or (ii) formulaic threshold-target-max goals. The relatively small weighting helps to evaluate performance holistically while still maintaining focus on delivering pre-established financial targets.

Bifurcate or Truncate STI and/or LTI Performance Periods

A more wholesale change is to bifurcate the performance period of an annual incentive plan (e.g., two six-month periods versus one annual period) or truncate the performance period of a long-term incentive plan (e.g., one-year or two-year goals with additional vesting versus three-year goals). Shortening a performance period was a frequently considered approach during the pandemic, but it was primarily used as a temporary tool against historic levels of uncertainty. Companies that try to implement these types of risk mitigation tactics now may face external criticism, particularly when the changes weaken the relationship between pay and performance.

For an annual incentive plan, six-month performance periods work best in support of businesses with seasonal operating models. Some companies apply more weight to the fall/winter season (e.g., 30% spring/70% fall) to align with higher sales volume during the holidays. Two six-month performance periods allow companies to set more accurate goals, provide two discrete opportunities to earn an annual incentive payout and use information gleaned in the year’s first half to set goals for the second half.

This approach avoids a zero-payout due to poor forecasting. It also provides year-long employee motivation, especially when performance gets off to a slow start or is affected by unforeseen macroeconomic events.

That said, it’s also important to be aware of the negative externalities. For example, management teams could become more short-sighted, as they may be disincentivized to fund projects with a timeline greater than six months but not quite long-term (e.g., nine months) because doing so could result in poor performance in one of the two performance periods. Additionally, compensation committees could need to consider utilizing negative discretion. Companies with financials that perform above threshold in the first performance period but not in the second could find themselves paying out on an annual incentive despite poor full-year performance.

For a long-term incentive plan, a shortened performance period signals that companies are having trouble predicting more than one or two years into the future. Investors and proxy advisors have demonstrated their opposition to this approach in the past; however, external reception highly depends on a company’s performance, ownership structure, historical design precedent and rationale.

Companies that would first incorporate this approach in light of low payouts could expect less leeway with investors. Organizations should consider the following questions when evaluating this approach:

- Is the organization able to set long-term goals?

- Are other reasonable metrics available: relative metrics, margins, and/or enduring standards?

- Have recent long-term incentive payouts appropriately reflected actual performance?

- Is there an opportunity to keep a longer performance period in a portion of the plan (e.g., a three-year TSR modifier or financial governor)?

Evaluate Relative Performance Rather Than Absolute Performance

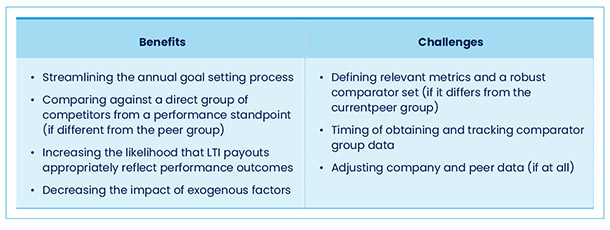

Relative financial metrics (other than relative TSR) can be a viable alternative for companies that cannot confidently set absolute goals. Whereas absolute metrics heavily rely on a company's ability to forecast into the future (e.g., three years or more), relative metrics afford companies a meaningful way to define pay for performance during periods of uncertainty.

Shifting to a more relative goal-setting approach has advantages and drawbacks:

Tactically, companies will need to make two key decisions to incorporate relative metrics: (i) which metric to evaluate relative to comparators and (ii) the relevant comparator set used for evaluation. Companies should consider external communications to investors (e.g., top strategic priorities, guidance, and relevant peers) and key performance measures (e.g., areas of improvement or strength) when evaluating these two decisions. For example, are investors more concerned with the company's performance relative to its peer set, a more bespoke performance comparator group or an industry index?

Committees should consider the durability of changing performance periods: whether the change would be a temporary adjustment to address FY23 uncertainty or something more permanent. Companies that seek longer-term solutions may benefit from an alternative approach (e.g., incorporating a strategic scorecard).

Principled Approach

Actions to mitigate goal-setting uncertainty should be rooted in key principles of incentive design and have a clear rationale.

Most retailers heading into FY23 may evaluate these approaches to reinforce pay and performance alignment, increase confidence that incentives will deliver fair payouts and reduce the impact of factors outside a company’s control. Companies must keep management teams and retail associates engaged for the entire fiscal year, regardless of the chosen approach. Given the ongoing uncertainty, it will be necessary for companies to balance employee motivation with fair outcomes for shareholders when constructing incentive plans for the upcoming year.

Companies should be mindful of the long-term durability of incentive plan changes and the impact of one-time actions versus permanent solutions.

Editor’s Note: Additional Content

For more information and resources related to this article see the pages below, which offer quick access to all WorldatWork content on these topics: